Peering from street level, it’s too dark to see how far down the manhole goes. Keeping a grip on the icy tarmac, I sit on theedge and lower myself gingerly onto the steel ladder. With rungs at least a foot apart, each step is a lurch into the unknown. Three metres down, I make a final jump to the ground and squint into the pitch black. The air is thick and it’s silent, save for the sound of water rushing around my ankles. Our guide Vlad Vozniuck scrapes the steel cover shut, cutting out the only shaft of sunlight and our portal to the outside world.

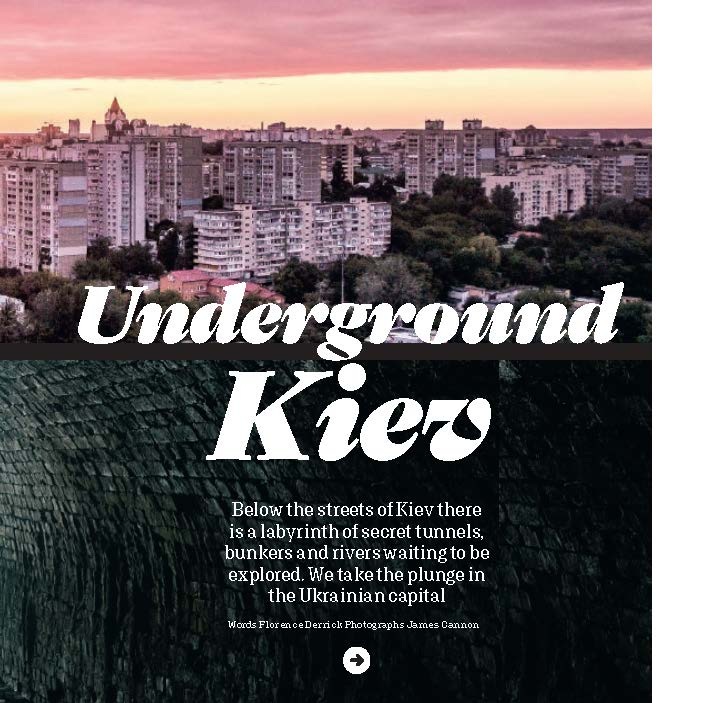

I’m in the Ukrainian capital city of Kiev. It’s -4°C and snowing outside, but underground it’s significantly warmer, a consistent nine degrees above freezing – a fact that eased my trepidation as Vozniuck whipped out a wrench and lifted the manhole cover.

Vozniuck is the founder of Urbex, an urban exploration company that takes tourists into underground Kiev, and the drainage systems and bunkers that lie beneath ground level. He has expert knowledge of these dark pathways, having explored the networks since he was 15.

“I first found an underground tunnel flowing out into the river. I got a torch, and with a friend went inside,” he remembers. “We turned a corner and saw that one tunnel became three. I then understood that under Kiev there was a big system of tunnels and you can go from one place in the city to another with them. I started to explore.”

Now 29, Vozniuck organises tours with his four explorer colleagues, and takes tour groups of up to 12 underground and to abandoned buildings every day. “It was an experiment, we had no idea if people would be interested or not,” he says. “But we put photos online and people started saying, ‘wow, can I go there?’ After that, we started making tours.”

We take our first steps into the tunnel, adjusting to darkness only alleviated by the dim light of our head torches and trying not to slip on the wet bricks underfoot. This underground passage, Vozniuck tells me, is the Hlybochytska river.

“Kiev is unique because of its underground rivers,” he says. “If you look at a map of the city, there are a lot of hills. One thousand years ago, there were rivers between them. As the city developed, planners buried them in tunnels under the streets. These rivers have historical names and usually the streets above share the same name.”

The river runs beneath Hlybochytska Street – the main vein of one of Kiev’s hippest districts, Podil. It’s home to basement bars, co-working spaces, street art and some of the city’s most remarkable architecture, including the imposing Zhitny Rynok – a brutalist, Soviet marketplace.

We turn into a narrower tunnel just a metre wide, with soft mud underfoot. With each squelchy step the mud attempts to pull off the ex-Soviet gumboots Vozniuck has loaned me. Seeing my worried face, he assures me that we won’t be encountering any sewage during our tour.

“In nearly every European city, if you open a manhole it’ll smell, because they have sewage systems that mix with drain water and underground rivers,” Vozniuck says. “But at the end of 19th century our engineers divided the sewage and underground water systems, so our underground rivers have clean water.”

Vozniuck knows all this from first-hand experience, as he’s part of a worldwide community of urban explorers, which he discovered through online forums as a teenager. They explore underground, climb deserted buildings and share their experiences on the internet.

“Now we’re all friends and we travel with each other to explore different places,” he says. “We have international meetings where we throw parties for 60 or 70 urban explorers from all over the world – all held underground, of course.”

Vozniuck’s travels have led him to ex-military bases in Albania, London’s sewers, deserted Italian castles and Russian space shuttles lost in the Kazakhstan desert. But Ukraine is uniquely primed for subterranean exploration due to two factors: its fascinating Soviet history, which saw some 550 Cold War bunkers built beneath Kiev alone, plus its 750km of underground rivers and 53km of drains; and a hangover from post-Communist law, which means that the trespassing laws of western Europe don’t apply in Kiev.

“Ukraine came from the USSR where everybody had common property,” Vozniuck explains. “Now, we have public and private areas but historically everything belonged to everyone. And still, Ukrainian underground bunkers belong to the city common property department. It means that if I’m a citizen I also pertain to a small part of this infrastructure.” It means that there aren’t laws to prohibit citizens like Vozniuck from exploring abandoned areas, although he gets personal permission from property owners when applicable. That said, it’s only advisable to explore the depths of Kiev with an expert guide – and Urbex is the city’s sole urban exploration company.

As we follow the path of the river, we pass graffiti and candle sticks melted onto ledges on the brick walls – evidence of the Ukrainian subculture that uses these underground networks for parties and to escape the punishing winter weather, which drops to -30°C in February. A risk of flash flooding means that Urbex only takes tour groups to the underground rivers in the summer – a heavy downpour can fill the tunnels to head height in 10 minutes – but the drainage systems, which also house bats, are safe to explore year round.

Part of the Urbex experience is facing absolute darkness and quiet. One of Vozniuck’s tricks is to leave visitors alone for five minutes, torches extinguished, in total silence. “People can hallucinate and think they hear voices far away in the tunnels, that aren’t there,” he says. Yet that’s nothing compared to some of his own subterranean experiences. He once spent 10 days below ground in Ukraine’s Blue Lakes, a four-hour drive from Kiev.

“After a few days you lose sense of day and night, and start having very colourful dreams, because everything you see when you’re awake is grey,” Vozniuck tells me. “All you hear is absolute silence. At first you hear yourself breathing and your footsteps. After five days you start to hear your own heartbeat. You become very aware of yourself.”

It’s intense stuff – and I’m slightly relieved when our torches shine onto the ladder that’ll lead us back to ground and almost blindingly bright daylight. But the excitement isn’t over yet. For the second part of the tour, Vlad drives us past Kiev’s historical landmarks – its answer to the Statue Liberty, the Motherland Monument; the National Opera House; and the gold-domed Saint Sophia’s Cathedral – to a grey tower block in a secret location.

We enter through a tall metal gate and are waved through by a security guard keeping warm in a Portakabin. From there, we crawl down a narrow stone tunnel and emerge in a gloomy concrete room secured by thick, iron doors. The labyrinth of rooms that follow are filled with protective rubber clothing, medical kits and radiation detectors – and space for 600 people to shelter. The bunker, which was thankfully never used, was built in 1986 at the tail end of the Cold War.

“This is not a museum,” Vozniuck says, encouraging me to pick up and inspect the objects we come across. “People can touch and explore. They feel like they’re part of the discovery, which is what makes it so interesting. We have just two rules: don’t take anything, and don’t touch any wires.”

Vozniuck’s colleagues discovered this bunker a year ago, left completely untouched since the Soviet Union broke down in 1991. It’s a huge thrill to be transported back in time to what was such a key moment in Kiev’s history. The musty air is loaded with an eerie atmosphere and the boxes of never-to-be-used equipment leave an impression that would be impossible to glean from behind glass in a museum.

We spend a good hour walking around, shining our torches on each corner of the bunker before Vozniuck leads us reluctantly back to ground level. Emerging from the snowy opening, grubby from the tunnels and faces lit with head torches and ear-to-ear grins, we’re met by a family sitting on a bench and tucking into a picnic lunch. They stare at us, aghast, as we brush ourselves off, give them a wave and trudge back to the car, totally exhilarated. Our next adventure? The search for the perfect chicken Kiev… urbextour.com