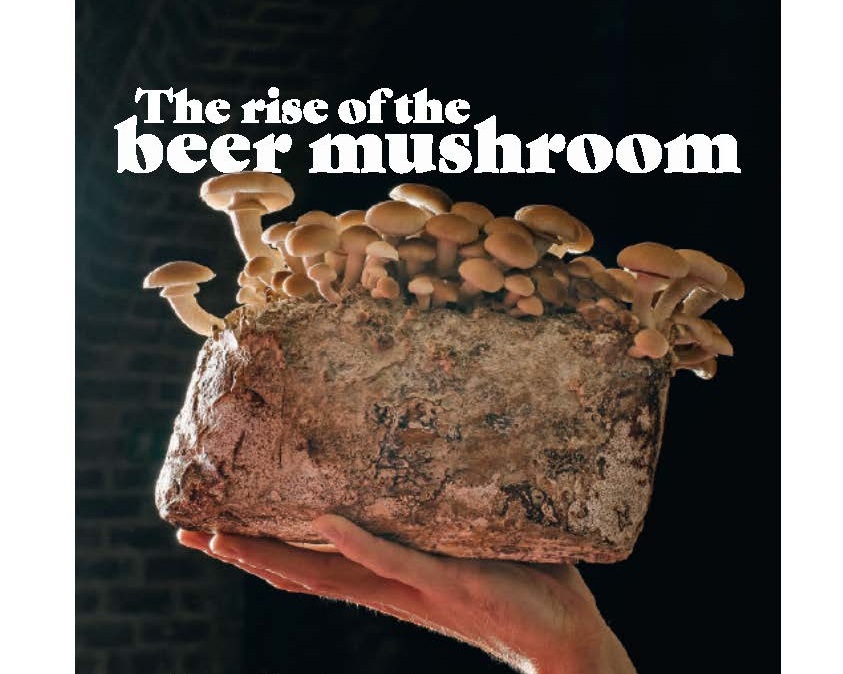

At the end of the warren of dimly lit tunnels is an opaque, plastic-sheet doorway. Easing it open, I step into the cool, humid greenhouse beyond. Above my head, a nozzle sprays mist into the air that’s already clouded with condensation. On metal shelves, lined out in rows, are rock-sized lumps of a spongy, brown-coloured substance, with a dense white fungus spreading over their surface. Thick-stemmed, earth-brown mushrooms protrude out, clinging to the edge as they sprawl into clusters, some as big as my fist. A man dressed in plastic protective clothing takes hold of one of the largest, and slices through its meaty stem with a knife, placing the harvested fungi in to a crate.

The whole scene has the air of an alien autopsy about it. “Mushrooms are one of the most mysterious living organisms,” agrees biologist Sylvère Heuzé, who fell for fungi when he encountered rural mushroom growers during his study abroad in Mexico. He’s one of four core members of staff at Le Champignon de Bruxelles, a specialist urban mushroom farm that was set up in 2014 and is based in the Caves de Cureghem: the cool cellars beneath a fruit and vegetable market-cum-abattoir in the Anderlecht district of Brussels. Originally built in the 19th century as foundations to support a livestock market upstairs, the cellars were repurposed to cultivate mushrooms in the early 20th century, before being converted into an occasional events space since the 1990s.

The start-up has colonised 1,000 square metres of the brick-roofed, underground alcoves, and each week produces a tonne of specialist, organic mushrooms to be delivered to the chefs and organic grocery stores of the capital. But these fungi are special for a reason other than plugging a gap in the market for shiitake, maitake and nameko mushrooms (which are almost impossible to buy elsewhere for a reasonable price). They’ve been cultivated on a waste product that comes from the most Belgian of industries: beer.

“I wanted to grow shiitake mushrooms because I knew there was a market for them here, and I began experimenting growing them on coffee waste first, in 2014,” says CEO Hadrien Velge, a trained economist with a specialist interest in social enterprises. “But I found it didn’t work very well, and there was already another producer in Brussels growing oyster mushrooms on coffee grounds. That’s when I thought of using beer waste – there’s a lot of it in and around Brussels and I’d heard that it could be used as a substrate for mushrooms. I realised quickly that it was much more effective than coffee waste, and no big producers were using it.”

It was at that point that bio-engineer Thibault Fastenakels joined the team, with the task to build the Cureghem cellar farm, which the small enterprise expanded into in 2016. Fastenakels, like Heuzé, is a fungus fanatic on a mission to bring the science and manual joy of agriculture to the inner city. “Mushrooms can grow on a lot of stuff that could generally be considered as waste,” he explains. “I like that we can produce a lot on a small area, in comparison with salad or potatoes, which need thousands of square metres. It’s interesting in an urban area.”

These aren’t the only Cureghem-based entrepreneurs with a passion for urban agriculture. On the roof of the same building is BIGH, Europe’s largest urban rooftop farm, where cherry tomatoes, basil, parsley, kale and more are lovingly grown, packaged and sold to supermarkets including Carrefour. And in Belgium, there’s a growing appetite for organic produce. Up to 90% of Belgians buy an organic product at least once a year, and the consumption of organic food increased by 6% between 2016 and 2017. In the midst of the growing global conversation on food sustainability, Velge and his three other ‘musketeers’ chose the perfect moment to launch their food-from-waste endeavour.

So how exactly are mushrooms grown from beer waste? On a tour of the facility, head of communications Quentin Declerck explains that only 10% of the ingredients used to make beer end up in your pint glass – and the waste product they use, called bierbostel, is the damp, protein-rich grain left over once the beer has been filtered. It makes an ideal breeding ground for mycelium fungus bacteria to grow on. The first hurdle, however, is finding an organic brewery to work with that can tie in with Le Champignon de Bruxelles’ pesticide-free ethos.

“It’s hard to find organic beer, because brewers have difficulties finding organic barley,” reveals Declerck. “We work with Cantillon, which is close to here and has a specific way of making gueuze [lambic] beer. They don’t put artificial yeast in it; instead they leave their vats open to the air and use the natural yeast from the building, which drops down and colonises the beer. It gives the beer its acidic flavour, and it’s organic.”

One of Le Champignon de Bruxelles’ 12 employees collects the bierbostel on a bicycle and brings it to the Cureghem HQ, where it’s pasteurised by heating it to 90°C for four to five hours. “Pasteurising keeps the good bacteria and kills the bad ones,” says Declerck. Then, the substrate is divided into plastic bags, the mushroom mycelium is added, and it’s incubated at 22°C for two to three months. During this time, the fungus colonises the beer substrate, producing heat and condensation that drips down the bag’s interior. “It’s 90% humidity in the bag,” explains Declerck. “The mushrooms are breathing, taking in oxygen and giving out CO2, which is why we have 20 kinds of microgreens growing here, too, which need CO2.” He gestures at some LED-lit shelves of herbs and spices – mini coriander and purple radish sprouts, as well as some specialist varieties like Japanese basil, to be sold directly to chefs. It’s a secondary part of the business, but vital to its philosophy of turning every waste product into a resource. The microgreens also provide a supplementary source of summer income, when mushroom sales are lower.

Once the mycelium has colonised the entire block of substrate, the plastic bags are burst open and the substrate is transferred from ‘summer’ weather in the hot incubation room to the cooler, autumnal greenhouse, where the temperature sits between 11°C and 15°C – the perfect climate for mushrooms to reproduce in. “Shiitake mushrooms stay in the greenhouse for just one week,” says Declerck. “Just opening the bag gives them a lot of oxygen, and they reproduce like crazy, by growing mushrooms. Once we’ve harvested them, we put the substrate into compost.” As for the mushrooms, they’re boxed up (using non-plastic packaging wherever possible) and sold immediately, always just a day or two old by the time they reach the shelves or a restaurant plate.

Stepping out of the misty autopsy room, I’m met by the welcome scent of frying mushrooms. Declerck sloshes thick soy sauce over the sliced shiitakes and lets them caramelise over a medium flame. He pours a glass of fluorescent-orange Cantillon beer and places it before me, alongside a small taster plate of soy-glazed shrooms. I dig in. The flesh is meaty and springy, while the flavour is deeply nutty and umami. As for the gueuze beer, it’s shockingly acidic – almost like a strong, UK West Country cider – and balances out the savoury mushrooms beautifully.

As we eat, I notice that the wall behind us displays a ‘circular economy’ chart, which shows how each waste product in the food industry can (and arguably should) be repurposed into a sustainable resource. “Here in the city, we have a lot of organic waste that can be used as a resource,” says Velge. “It’s a vehicle to produce food locally with the resources we have available, which I think is the most important thing right now.”

For Heuzé, growing mushrooms this way sets a perfect example for food sustainability solutions. “Mushrooms are a recycling organism,” he says. “In any part of the world, you will always have organic waste – a resource that is free, and in very big volume – that you can use to make mushrooms. It can be developed for food security. A little rice producer in Asia, for example, could have a secondary activity to make mushrooms. You don’t even need any technology – it can be as simple as adding water to straw.”

Their enthusiasm is infectious and is the backbone of their cooperative setup. Fifty investors and co-op members have a say in every company decision made in these vaults. It’s an unusual approach, which works thanks to a common desire to help the enterprise thrive. So what’s next for Belgium’s subterranean mushroom men?

Declerck picks up a bag of substrate that’s incubating in a corner shelf, separate from the rest: an experiment. I peer closer, observe its rich-brown colour and detect a sweet, familiar scent.

“Cocoa beans,” says Heuzé with a huge grin. “They are from the chocolatiers in Brussels. It’s still in development but we’re hoping to grow mushrooms from it next year.” Mushrooms don’t get much more Belgian than that. lechampignondebruxelles.be

One reply on “Magic mushrooms: the rise of the beer mushroom in Brussels”

This article is very helpful. Thank you for sharing this information. It is amazing how mushrooms are grown from the waste of beer. Now, I know that it is possible to grown mushrooms from a waste of beer.